What Happened On September 30th?

On September 30, 1949, the sound of aircraft engines over West Berlin came to a halt, bringing the Berlin Airlift to a close. The final flight landed, completing an operation that had delivered over two million tons of supplies in 277,000 flights. The Allies ensured that this last shipment carried vital goods, just as every flight before it had. West Berliners, who had faced starvation and isolation under Soviet blockade, saw their city endure thanks to this relentless effort.

At Tempelhof Airfield, workers unloaded the final cargo with the same precision they had maintained throughout the airlift. For months, these crews had worked tirelessly, understanding that each plane carried the essentials that kept the city alive. The last plane landed without fanfare, but the workers recognized the gravity of the moment. By the time the final shipment was processed, West Berlin had built up enough reserves to protect its future. Tempelhof, originally designed as a regional airport, had handled far more traffic than anyone could have predicted.

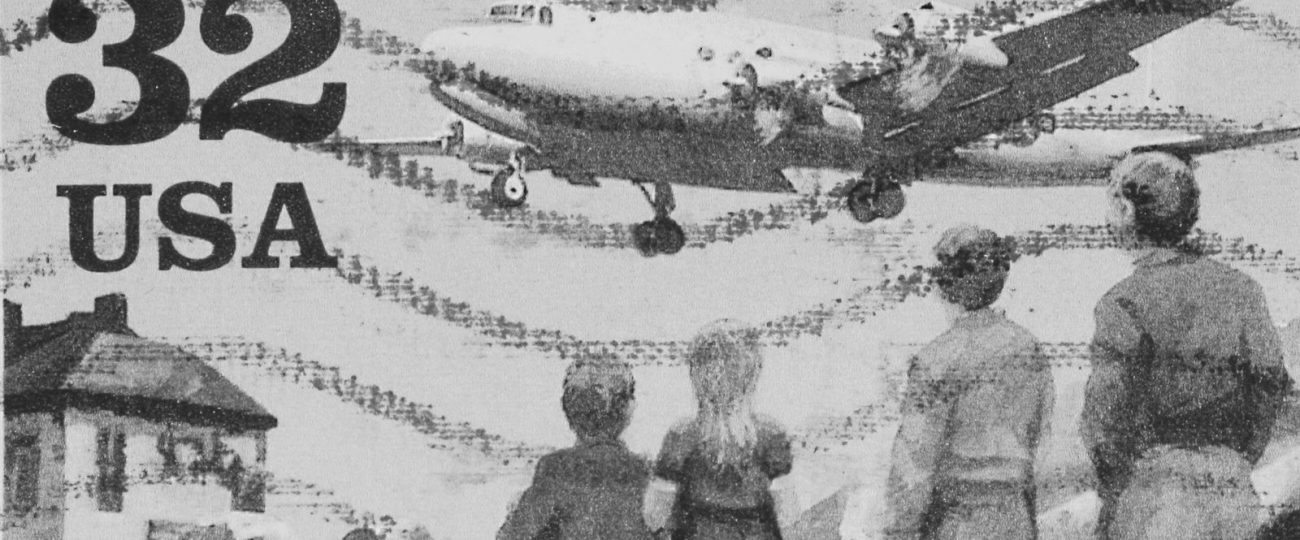

Pilots, who had flown through narrow air corridors and faced dangerous conditions, understood the importance of their last landing. After months of dodging Soviet interference, mechanical failures, and brutal weather, they had completed a mission many had doubted was even possible. Berliners gathered around the airfields to watch the final landings, knowing their city had survived because the Allies never gave up. Pilots remembered the challenges of landing in dense fog, relying solely on instruments to guide them safely onto the runways.

The planes, now grounded on the airfields, represented more than just logistical success. They demonstrated the determination of both Berliners and the Allies, who refused to let the city fall to Soviet pressure. The airlift had kept the city alive and demonstrated the unity of the Western Allies in action. Ground crews, who had worked without pause for over a year, now had the chance to reflect on their achievement. More than 2,000 crew members had kept the steady flow of flights moving, ensuring no delays. Their efficiency allowed planes to be refueled in under 10 minutes, a key factor in maintaining the airlift’s constant pace.

Berliners, who had grown used to the constant sound of aircraft overhead, immediately noticed the sudden quiet. For more than a year, the steady drone of planes had been the city’s lifeline, with every flight bringing food, coal, or medicine. Now, with the skies silent, Berliners could look back and grasp how close they had come to collapse and how the airlift had saved them. Families who watched the planes land from their rooftops recalled the speed and precision with which the crews worked, while children turned plane-spotting into a game, identifying aircraft by the sound of their engines.

The success of the airlift depended not just on the pilots but also on the ground crews who ensured the operation ran smoothly. At the height of the airlift, planes landed every 45 seconds in West Berlin, and ground crews unloaded, refueled, and prepared them for takeoff in record time. Tempelhof and Gatow airfields, which had not been built to handle such heavy use, became the core of this enormous logistical effort. Crews expanded the airfields, lengthening runways and building makeshift hangars to keep the operation going. The speed and precision with which they worked ensured that no plane stayed on the ground longer than necessary.

The pilots faced constant dangers on every flight. They navigated through narrow air corridors, always aware of Soviet attempts to interfere with their missions. Though the Soviets never directly attacked, they flew dangerously close to the Allied planes, jammed radio signals, and tried to disorient the pilots with searchlights during night flights. Weather often proved an even greater challenge, forcing pilots to land in dense fog, rain, and freezing conditions. Despite these obstacles, the flights continued without interruption. When a plane carrying coal crashed near the city, Berliners quickly salvaged the cargo, refusing to let any vital supplies go to waste.

The airlift didn’t just provide essential supplies; it also gave Berliners a sense of hope. Gail Halvorsen, known as the “Candy Bomber,” became famous for dropping candy to the city’s children. His small act of kindness, which began as a personal initiative, turned into “Operation Little Vittles,” and by the end of the airlift, more than 23 tons of candy had been dropped over West Berlin. Halvorsen’s efforts showed Berliners, especially the youngest among them, that they were not alone in their struggle. Many of the pilots involved in the airlift developed lasting connections with the city, returning years later to visit the children they had once flown candy to during those challenging times.

Berliners themselves played a vital part in ensuring the airlift’s success. Tempelhof’s runways, never intended for such intense use, required constant maintenance. The Trümmerfrauen, women who had already worked to clear rubble from the bomb-damaged city, took on the task of repairing the airfields. Using whatever tools they had, they filled craters, smoothed runways, and kept the airfields functional, despite the difficult conditions. Their efforts, especially during the harsh winter months, kept the airlift from facing any major interruptions.

British and American cooperation was essential to the success of the airlift. The British Royal Air Force, which had initially focused on delivering food, modified their planes to carry coal as winter approached. Bombers, once built for warfare, were transformed to carry coal to keep the city warm. The British and American forces coordinated closely, sharing resources and managing flight schedules to keep the supply line intact. The British crews even developed special winches to load coal more efficiently, preventing spillage and maximizing the amount delivered per flight.

Although the official end of the airlift came on September 30th, planes continued flying into Berlin for several weeks afterward. These flights, often without cargo, served as a demonstration to the Soviets that the Allies could maintain the airlift for as long as necessary. The empty planes carried political weight, making it clear that West Berlin would remain connected to the West, no matter what the Soviets tried.

By the time the last flight touched down, the Allies had delivered over two million tons of supplies to West Berlin, ensuring the city’s survival. The airlift proved that the Western powers would not abandon the city, no matter how difficult the circumstances. The operation was more than a logistical feat—it built a lasting bond between Berliners and the Allies, one that would endure long after the final plane had landed.