What Happened On September 22nd?

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln called his cabinet together at the White House. After the Battle of Antietam, which had halted the Confederate advance, Lincoln knew it was time to act. He had held onto the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation for months, waiting for the right moment to release it.

Lincoln had drafted the proclamation in July, but he had chosen not to issue it during the Union’s earlier military setbacks. He wanted to introduce it from a position of strength. After Antietam, he believed the time had come. He read the document aloud to his cabinet, stating that as of January 1, 1863, enslaved people in states still rebelling would be “forever free.” The proclamation did not apply to the loyal border states or areas already under Union control. Lincoln had carefully crafted the language to avoid alienating Union states where slavery still existed, while targeting the South’s economic system.

Lincoln’s cabinet listened closely. Secretary of State William Seward, who had earlier advised Lincoln to wait for a Union victory, supported the move. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, though preferring a stronger stance, understood the need for Lincoln’s approach. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair expressed concerns about the political risks in the upcoming elections, but Lincoln held firm. He believed that the time to act had arrived.

By that afternoon, Lincoln finalized the proclamation. He made it clear that rebellious states had until January 1st to return to the Union, or they would lose their enslaved labor force. Although Lincoln framed the proclamation as a war measure, it took a large step toward ending slavery in America. News spread quickly across the country, with newspapers rushing to print it.

That evening, responses came in from every corner of the country. Abolitionists praised the decision, while some Northerners worried about its economic consequences. Northern Democrats, especially the Copperheads, denounced it as an abuse of power. Despite the divided opinions, Lincoln understood that the proclamation had reshaped the war’s meaning. It was no longer just about preserving the Union—it had become a fight for freedom.

Lincoln, tired after a long day, later reflected on the decision he had made. He told Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that issuing the proclamation had been one of the hardest choices of his presidency. Although Lincoln had always opposed slavery on moral grounds, he had waited to act, aware of the political risks. Now, with the war still raging and victories rare, Lincoln seized the chance.

In Richmond, the Confederate capital, leaders reacted with fury. Southern newspapers called the proclamation an attack on their way of life. Jefferson Davis condemned the proclamation as an act of war and threatened retaliation against Union officers enforcing it. The South became even more determined to fight on, unwilling to submit to Lincoln’s terms.

In the North, Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists celebrated the proclamation. Douglass, who had long urged Lincoln to take action against slavery, immediately saw its importance. He encouraged Black men to enlist in the Union Army, knowing that their service could help secure their freedom. By the end of the war, more than 180,000 Black soldiers had joined the Union, many driven by the promise of emancipation.

Not everyone in the North reacted favorably. In cities like New York and Boston, some feared that the proclamation would lead to an influx of freed slaves competing for jobs. Labor tensions rose as workers worried about their livelihoods. Despite these concerns, Lincoln pressed forward, understanding that the proclamation had redefined the war’s objectives.

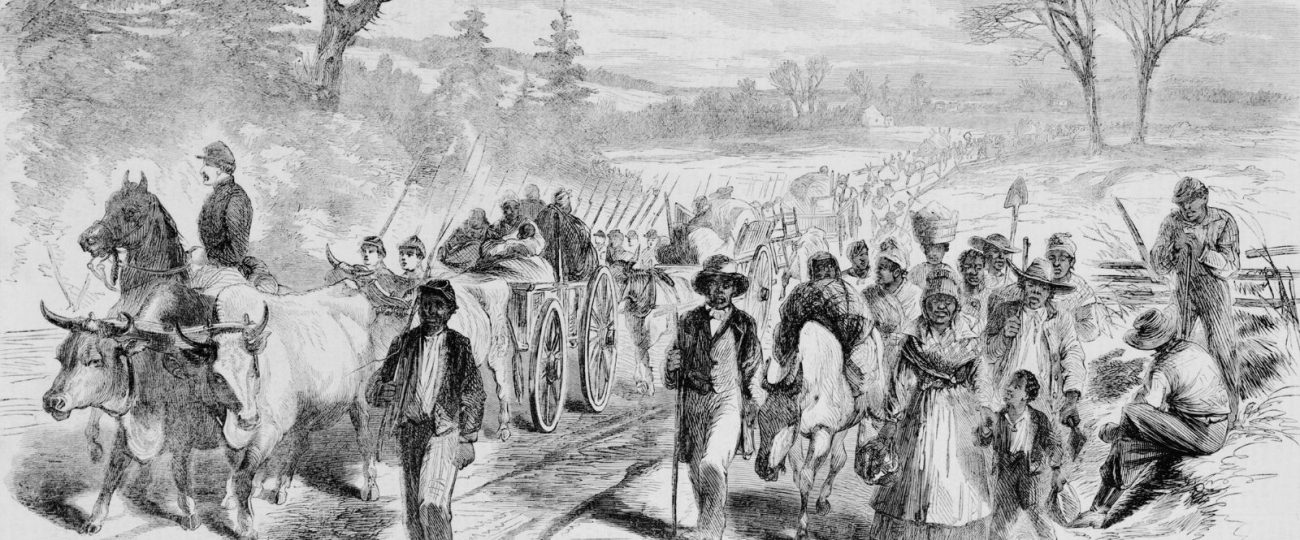

In the South, enslaved people heard about the proclamation through word of mouth and from Union soldiers. Many took the opportunity to flee plantations and seek refuge behind Union lines. Although the proclamation didn’t immediately free anyone, it gave hope to thousands of enslaved people. Their exodus from plantations weakened the South’s labor system and created new difficulties for the Confederacy.

Union generals, such as Benjamin Butler and Ulysses S. Grant, had already seen enslaved people escaping to Union camps whenever Union forces neared Confederate territories. Lincoln’s proclamation gave them authority to protect those seeking freedom and encouraged more to escape. Union camps quickly filled with thousands of formerly enslaved people, many of whom enlisted in the Union Army to fight for their freedom.

Lincoln had prepared carefully before issuing the proclamation. He consulted legal experts, including Attorney General Edward Bates, to ensure the proclamation would stand as a wartime measure. Lincoln knew that the proclamation needed strong legal grounds to survive challenges in court. By framing it as a military necessity, he made it harder for critics to argue against its legitimacy.

Although the promise of emancipation gained the most attention, the proclamation also included a clause about colonization. Lincoln had previously considered compensating slaveholders and encouraging freed Black people to emigrate to colonies outside the United States. While the idea of colonization faded, its inclusion revealed Lincoln’s evolving views on how to manage the transition from slavery to freedom.

Confederate generals quickly reported that the proclamation had caused an immediate effect. Enslaved people began abandoning plantations in larger numbers, seeking freedom with the Union forces. Some plantation owners left their properties, unable to continue operations without enslaved labor. While the war continued, the proclamation began to tear apart the South’s economic foundation, just as Lincoln had anticipated.