What Happened On October 9th?

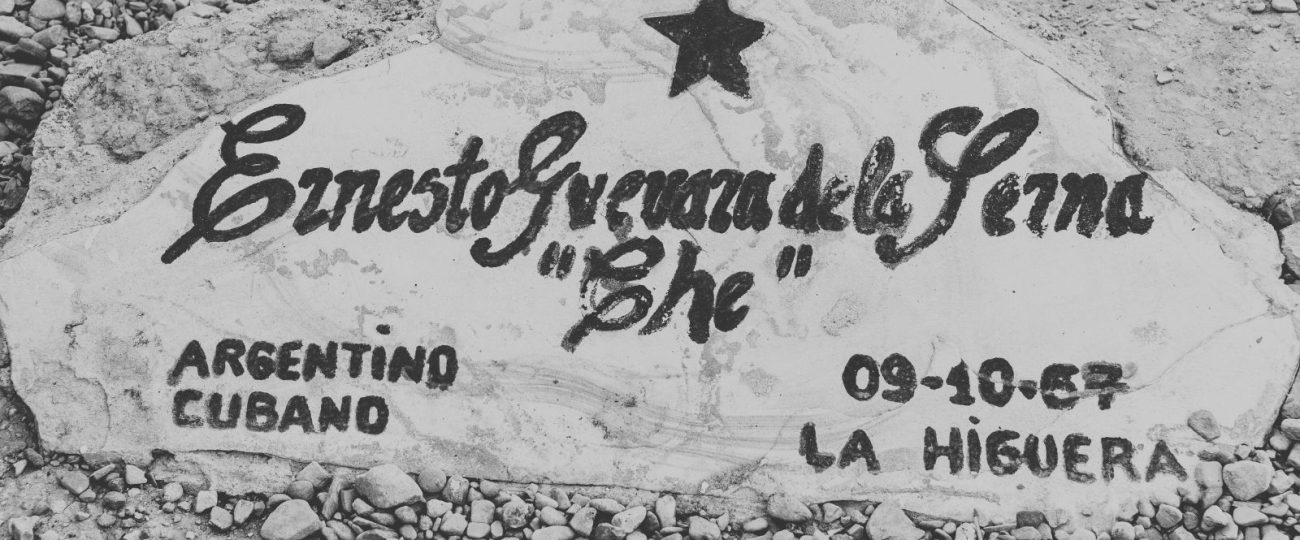

On October 9, 1967, Bolivian soldiers executed Ernesto “Che” Guevara in the village of La Higuera. Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, had become famous for his role in the Cuban Revolution of 1959, where he helped overthrow the U.S.-backed regime of Fulgencio Batista alongside Fidel Castro. After the Cuban success, Guevara set his sights on spreading socialist revolutions across Latin America, convinced that guerilla warfare was the path to liberation for oppressed peoples. His mission in Bolivia aimed to ignite a wider movement across South America, but it ended in failure and led to his capture.

By the time of his capture, Guevara’s campaign in Bolivia had all but collapsed. His guerilla group, operating in the rugged Bolivian highlands, struggled from the start. They faced difficult terrain, lacked local support, and were cut off from supply lines. The local peasants, whom Guevara had hoped to rally, instead informed the authorities of his movements, fearing retribution or hoping for rewards. Guevara’s situation worsened when Bolivian soldiers, supported by U.S. intelligence, closed in on his position in the Yuro Ravine. A brief firefight ensued, and Guevara, wounded and unable to escape, fell into enemy hands.

In the hours after his capture, the Bolivian military received orders to execute him. CIA agent Félix Rodríguez, who had tracked Guevara for months, arrived at the remote village to interrogate the captured revolutionary. Rodríguez later recalled Guevara’s unyielding demeanor during their brief conversation. Guevara did not provide any tactical information about his comrades or guerilla strategy. Instead, he condemned U.S. intervention in Latin American affairs. Rodríguez described him as calm and resolute, despite the impending execution.

The responsibility of carrying out the execution fell to Sergeant Mario Terán, a Bolivian soldier who had lost comrades to Guevara’s guerilla fighters. Terán hesitated as he faced the man who had gained international fame for his defiant revolutionary ideals. Guevara, aware of the hesitation, instructed him, “Shoot, coward!” Terán fired multiple shots, killing Guevara instantly. Guevara’s death, though an end to his Bolivian campaign, did not diminish his legacy. His revolutionary fervor and the circumstances of his death would resonate for decades.

After the execution, the Bolivian authorities transported Guevara’s body to Vallegrande, where they publicly displayed it to confirm his death. The government, eager to erase any doubt, invited journalists and locals to view the body. However, the act of putting Guevara’s remains on display had unintended consequences. The images of his body, serene and dignified, spread quickly around the world, fueling the narrative of Guevara as a martyr rather than suppressing his influence.

To further ensure that no rumors about his survival could emerge, the Bolivian military took the unusual step of severing Guevara’s hands. They sent the hands to Buenos Aires for fingerprint analysis, confirming his identity. Meanwhile, his body was buried secretly in an unmarked grave near Vallegrande, its location hidden for nearly thirty years. The mystery surrounding his burial only heightened the fascination with his life and death.

Guevara’s attempt to export revolution to Bolivia had faced immense difficulties from the start. Unlike in Cuba, where his guerilla tactics thrived in the mountains, Bolivia’s terrain and social conditions proved inhospitable. His guerilla group, numbering fewer than fifty, faced constant challenges, from the lack of local support to clashes within their ranks. The local Communist Party in Bolivia, which Guevara had hoped would be his ally, distanced itself from his efforts, and the Bolivian peasants whom he sought to liberate often sided with the government forces out of fear or distrust of his foreign-led movement.

Bolivian military forces, with CIA support, relentlessly tracked Guevara’s every move. The CIA provided the Bolivians with radio triangulation technology, allowing them to pinpoint Guevara’s location in the jungle. This technology, advanced for the time, played a crucial role in tracking Guevara’s guerilla force, who were already weakened by months of harsh conditions, illness, and dwindling supplies. By the time they cornered him in the Yuro Ravine, Guevara’s health had deteriorated significantly, making it impossible for him to evade capture.

During his final hours inside the schoolhouse, Guevara remained steadfast. Rodríguez, who witnessed the last moments, noted that Guevara refused to renounce his revolutionary beliefs. Despite knowing that death was imminent, Guevara accepted his fate without regret. His unbroken will in the face of execution only added to his enduring image as a revolutionary who remained true to his ideals until the very end.

The Bolivian authorities believed that burying Guevara in secret would diminish his influence, but the lack of a known grave only fueled speculation. For years, rumors circulated that Guevara had escaped death and would return to continue his revolutionary efforts. The absence of a marked burial site fed into the mystery, and instead of fading from memory, Guevara’s influence only grew in the years following his execution.

In 1997, Guevara’s remains were finally uncovered in a mass grave outside Vallegrande. A team of forensic experts from Cuba and Argentina verified his identity using dental records. Guevara’s body, which had been buried without its hands, was flown back to Cuba, where he was reburied with full military honors. His return to Cuba, the country where his revolutionary career had flourished, closed the chapter on the mystery of his burial, but his influence had long outgrown the limitations of his physical presence.

Guevara’s Bolivian campaign had been plagued by several strategic missteps. His small force, which operated without sufficient supplies or local support, struggled from the outset. The Bolivian peasants, whom Guevara had believed would join the revolutionary cause, instead turned against him. Many saw him as an outsider imposing foreign ideas, while others feared retaliation from government forces. Instead of igniting a regional uprising, Guevara found himself isolated in a hostile land where his revolutionary ideals failed to take root.