What Happened On October 28th?

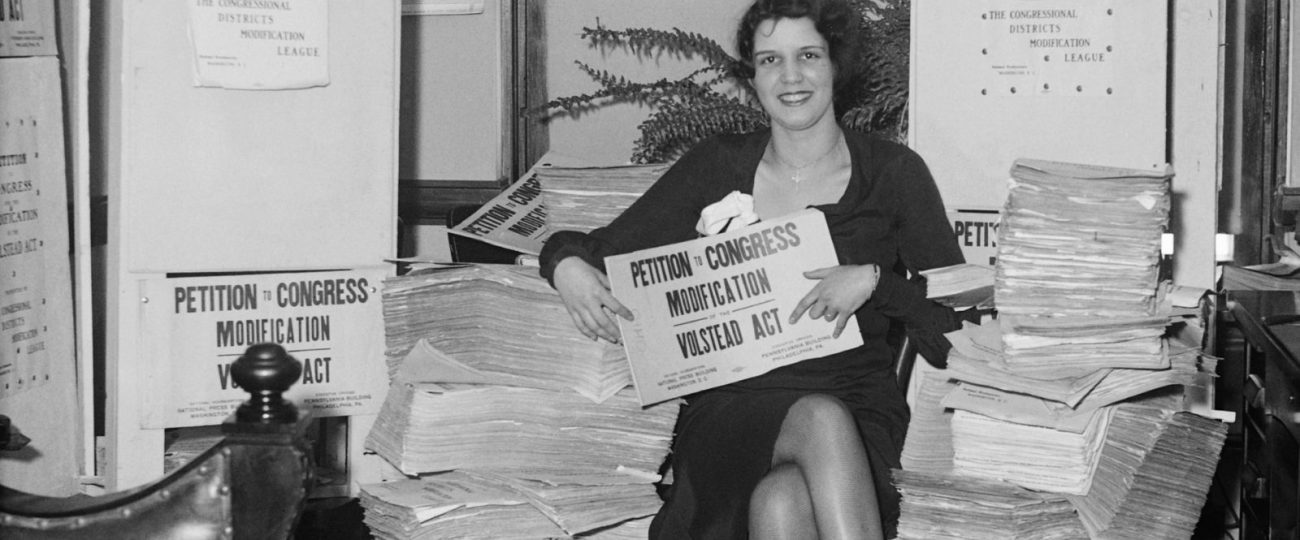

On October 28, 1919, Congress passed the Volstead Act, officially launching Prohibition in the United States. After President Wilson’s veto, Congress wasted no time in overriding him, setting into motion the national ban on alcohol. The act prohibited any beverage containing more than 0.5% alcohol, including beer and wine, which many had hoped would be exempt. The strict definition left no room for exceptions, causing frustration across the country, even though temperance advocates saw it as the culmination of their years of efforts.

Temperance groups such as the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union had long claimed that alcohol caused societal ills like crime, poverty, and family breakdowns. Their decades of campaigning intensified during World War I, as the government promoted grain conservation for food rather than alcohol. Anti-German sentiment also contributed to their success, as many brewers had German roots, making them easy targets for public criticism. The culmination of this pressure was the passage of the Volstead Act, which now made the federal government responsible for enforcing Prohibition.

The Volstead Act had some loopholes that many quickly exploited. Pharmacies continued to sell medicinal whiskey with a doctor’s prescription, and Walgreens grew its chain from 20 stores to more than 500 during the Prohibition years. This growth was partly fueled by the high demand for “medicinal” alcohol, which people could obtain legally despite the ban. Churches, too, saw an unexpected increase in membership, as sacramental wine remained legal for religious services. Many vineyards, particularly in California, shifted their focus to selling grape bricks—compressed grape concentrate—designed for home winemaking. These bricks included instructions on how to avoid fermentation, which most people interpreted as a guide for doing exactly that.

Speakeasies rapidly became a fixture of urban life. These hidden bars, operating in back rooms and basements, provided a place where Americans could still gather to drink. In cities like New York, speakeasies outnumbered pre-Prohibition bars, as their popularity soared. These secret establishments thrived with the complicity of local authorities, many of whom accepted bribes to allow their continued existence. The rise of speakeasies also led to cultural shifts. Women, who had traditionally been excluded from saloons, became regular patrons of these underground venues, pushing social boundaries and defying the restrictions of the era. Jazz music found a home in these establishments, making speakeasies central to the rise of the Jazz Age.

The impact on the brewing and winemaking industries was severe. Many breweries and vineyards either closed or drastically shifted their operations to survive. Some breweries adapted by producing sodas, malted milk, or near beer, a beverage with minimal alcohol content. Winemakers in California, who had thrived before Prohibition, turned to legal grape concentrate production to maintain some level of business. Though religious exemptions allowed for sacramental wine, this was not enough to sustain the industry. In some cases, entire vineyards were destroyed, and valuable grapevines were uprooted.

Enforcing the Volstead Act proved nearly impossible. The Prohibition Unit, part of the Treasury Department, faced corruption, understaffing, and insufficient resources. Many agents, poorly paid, accepted bribes from bootleggers and speakeasy owners, making enforcement more of a symbolic effort than a practical one. Organized crime flourished in the absence of effective policing. Figures like Al Capone built criminal empires, smuggling alcohol from Canada and Mexico, using bribes and violent tactics to control distribution. Smuggling, known as rumrunning, became a highly organized business, with fast boats and intricate supply routes allowing bootleggers to outmaneuver law enforcement.

Moonshining—the illegal production of alcohol—became widespread, particularly in rural areas. Hidden stills operated in remote regions, producing potent homemade liquor. Smugglers transported the moonshine to urban centers, where it was sold to speakeasies. This liquor was often dangerous, as poor distillation practices sometimes led to batches containing harmful chemicals like methanol. Despite the risks, moonshine remained in high demand, fueling the underground economy that emerged from the alcohol ban.

Prohibition led to significant shifts in drinking habits. Before the law, beer had been the most popular alcoholic beverage in America. However, its bulk made it difficult for bootleggers to smuggle, so they turned to hard liquor, which was easier to transport and much more profitable. As a result, Americans began drinking more spirits than they had before, a trend that lasted even after Prohibition ended. This change reflected not only the practicalities of smuggling but also the new social dynamics of the era.

The rise of speakeasies also contributed to a changing social landscape. Previously, drinking in public had been an almost exclusively male activity, but during Prohibition, women began frequenting speakeasies in greater numbers. These underground bars offered a space where women could socialize freely, challenging the traditional gender roles of the time. Speakeasies became places where jazz, dancing, and alcohol converged, creating a rebellious atmosphere that defined the Roaring Twenties. Drinking in these establishments carried an air of defiance, as patrons gathered not just for the sake of alcohol but to reject the moral restrictions imposed by the government.

Organized crime syndicates grew immensely powerful during this period. Bootleggers, who smuggled alcohol from abroad or produced it illegally within the U.S., became wealthy and influential. Criminal organizations like Al Capone’s in Chicago controlled not only the illegal alcohol trade but also other ventures like gambling and prostitution. Violence became a regular feature of urban life as gangs competed for control over territories and smuggling routes. The rise of these crime syndicates created an underworld that had deep political and social consequences.