What Happened On October 13th?

On October 13th, 1845, William Parsons, the 3rd Earl of Rosse, aimed the Leviathan of Parsonstown, his massive telescope, toward a nebula in Canes Venatici called Messier 51. The cold air and the enormous telescope’s scale required precise coordination as the crew worked together to position the instrument. The Leviathan, standing over 50 feet tall with a 72-inch mirror, was an engineering marvel for its time. That night, it revealed details that forever changed the field of astronomy.

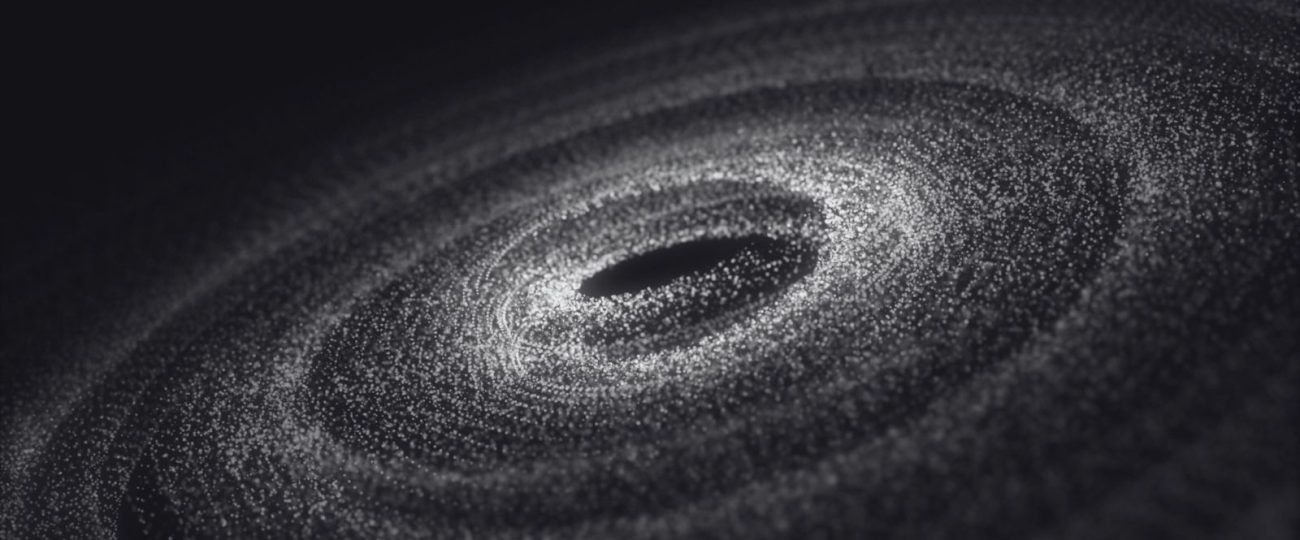

Parsons adjusted the telescope’s focus on M51 and saw much more than any previous astronomer had recorded. Instead of a faint, indistinct blur, he spotted spiraling arms extending from a bright central core. No one had ever documented such an image before. He called his assistants over to verify what he observed—distinct, curving arcs that made up a structure entirely different from what had been expected. They immediately began sketching, capturing every curve and swirl visible through the telescope’s eyepiece. These sketches laid the foundation for what we now recognize as the first detailed depiction of a spiral galaxy.

While sketching, the team also noticed a smaller object close to M51, which is now known as NGC 5195. Though they could not determine its connection to the larger spiral at the time, they recorded its position accurately, noting its impact on the surrounding structure. Modern astronomers later confirmed that this smaller galaxy was interacting with M51, pulling at its spiral arms through gravitational forces. Despite their limited understanding of these interactions, Parsons’ detailed observations offered an early glimpse into galactic behavior and structure.

The Leviathan’s construction had been a massive endeavor. Parsons and his team struggled through numerous attempts to cast the four-ton mirror, made of speculum metal, which tarnished easily and required constant maintenance. The metal’s fragility posed problems, and even slight imperfections during polishing could compromise their observations. Eventually, they succeeded, creating a polished, reflective surface that exceeded any other telescope at the time. On October 13th, that precision allowed the telescope to reveal the Whirlpool Galaxy in a way no other instrument could. The team’s perseverance proved their critics wrong, as many had doubted the practicality of such a large telescope.

Skeptics soon challenged Parsons’ findings. Some argued that the spiral patterns were illusions caused by flaws in the telescope’s mirror. To address these claims, Parsons instructed his team to create highly detailed drawings and descriptions of their observations, ensuring they documented every feature accurately. The quality of their work served as evidence against critics who questioned the validity of the spirals. Decades later, when photographic technology advanced, astronomers captured images of M51 that perfectly matched the original sketches, confirming that Parsons and his team had accurately recorded the structure.

The team’s sketches also captured intricate details about NGC 5195’s interaction with M51. While they could not fully understand the nature of this interaction, their documentation showed how the smaller galaxy appeared to distort the spiral arms of M51. Later research revealed that NGC 5195’s gravitational pull was responsible for these distortions. By observing and recording this phenomenon, Parsons and his team created a foundation for future astronomers to explore how galaxies influence one another.

Parsons’ success with the Leviathan inspired other astronomers to create their own large-scale telescopes. John Herschel, a prominent astronomer of the period, visited Parsons’ observatory and studied the telescope’s design. He applied many of its principles to his own instruments, which advanced the field of astronomy significantly. The Leviathan’s breakthrough encouraged others to build telescopes of similar scale, moving beyond the constraints of older models and enabling new discoveries.

The Whirlpool Galaxy remains an iconic subject for astronomers. Both professional and amateur observers frequently target it, using technology that is much smaller yet more advanced than what Parsons and his team had available. Today’s telescopes allow observers to capture images with clarity and speed that would have been unimaginable in the 19th century. However, the first glimpse of the Whirlpool Galaxy’s spiral arms came through the work conducted on that October night in 1845. Parsons and his team, through their careful and precise recording, provided the foundation for our modern understanding of spiral galaxies.

The telescope’s construction did not just involve scientific ambition; it included local craftsmen and workers from the Birr estate. Parsons recruited metalworkers, stonemasons, and carpenters from the area, turning the building of the Leviathan into a community effort. The telescope became a source of local pride, with the townspeople invested in its success. This collaborative spirit underscored the determination required to build and operate such an advanced instrument.

The Leviathan’s towering walls and massive structure also drew visitors from across Europe, making it a center for astronomical observation and discussion. Astronomers from as far as France and Germany visited to see the results of Parsons’ efforts firsthand. These visits fostered a community of scientists who exchanged ideas and advanced the study of astronomy collectively. The impact of the Leviathan went beyond just one telescope; it became a hub for a growing scientific community eager to push the limits of what they could observe.