What Happened On November 19th?

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln arrived in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to dedicate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Four months earlier, the land around the town had been the scene of one of the Civil War’s most brutal battles. The three-day conflict at Gettysburg left around 50,000 soldiers dead, wounded, or missing, marking a turning point in the Union’s efforts against the Confederacy. Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg to honor those who had perished and to bring hope to a divided nation. He spoke after Edward Everett, a well-known orator and former U.S. Secretary of State, who had spent two hours recounting the events and losses of the battle.

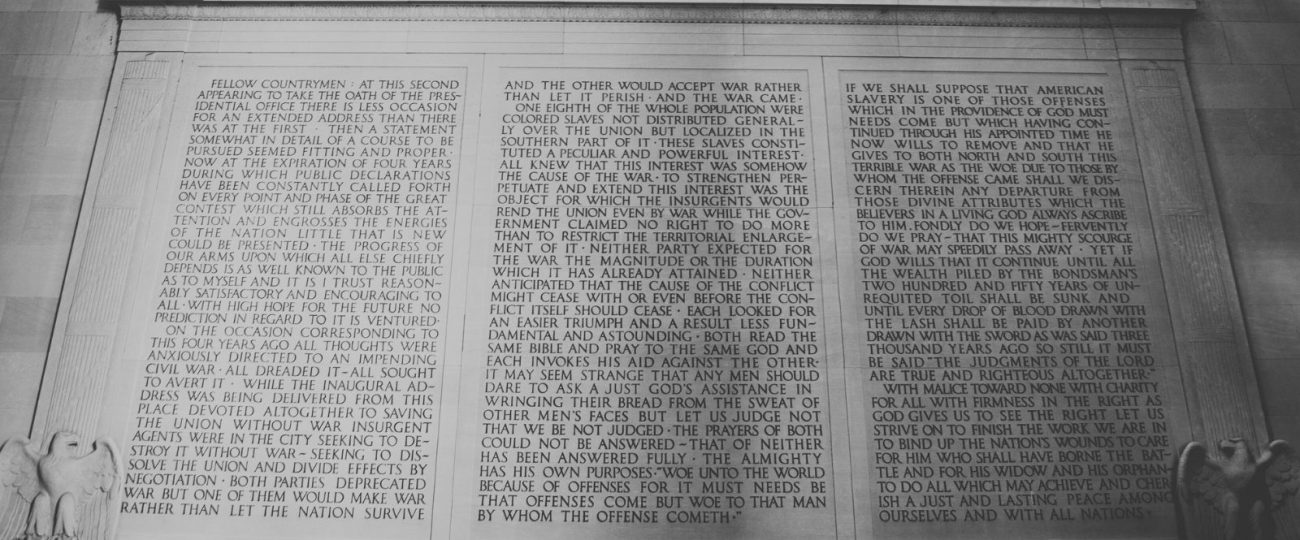

When Lincoln took the podium, the crowd fell silent. Dressed in his familiar black suit and stovepipe hat, he projected a calm yet solemn presence. He began with the now-iconic words, “Four score and seven years ago,” anchoring his message in the principles upon which the United States had been founded. Lincoln’s speech lasted just two minutes and contained 272 words, yet the clarity and gravity of his address struck the audience. His precise and direct message left a lasting impression on those who heard it.

Lincoln called on Americans to dedicate themselves to the cause for which the soldiers at Gettysburg had given everything. He framed the Civil War as a test of the nation’s commitment to liberty and equality, questioning whether a “government conceived in Liberty” could survive such a challenge. He promised that the dead had not given their lives in vain, urging renewed dedication to the principles of freedom.

Edward Everett, despite his lengthy address, later expressed admiration for Lincoln’s brief speech, saying he wished he had captured the sentiment “in two minutes” as Lincoln had. The Gettysburg Address soon became central to Lincoln’s legacy, capturing the ideals for which Union soldiers had fought and died.

Born on February 12, 1809, in a Kentucky log cabin, he grew up amid the hardships of frontier life. His formal schooling lasted less than a year, yet he educated himself, reading every book he could find on literature, history, and law. By his early thirties, he had established himself as a respected attorney, known for his honesty—a trait that carried him into Illinois politics. His character and straightforward approach earned him the nickname “Honest Abe,” a quality that would later define his presidency and connect him with ordinary Americans.

In 1860, Lincoln assumed the presidency of a fractured nation. Seven Southern states had already seceded, and his determination to preserve the Union soon shaped his leadership. Throughout the Civil War, Lincoln remained unwavering in his dedication to democratic values, guiding the nation through its darkest hours. His early “house divided” speech, in which he declared that a nation could not endure permanently half-slave and half-free, reflected his deep conviction about unity and equality.

Despite the reverence it receives today, the Gettysburg Address initially drew mixed reactions. Some newspapers praised its elegance, while others dismissed it as too brief. The Chicago Times criticized it as “silly, flat, and dishwatery.” Over time, however, Americans recognized its significance. By the end of Lincoln’s life, the address had become an expression of national values, memorized by schoolchildren and cited by public figures.

Lincoln’s influences for the speech came from his lifelong reading of the Bible, Shakespeare, and classical works, which shaped the rhythm and style of his words. He used phrases like “fourscore and seven” to echo biblical language, while the structure of his address displayed his understanding of classical oratory. His ability to distill complex ideas into concise, meaningful language reflected both his intellect and his gift for communication. Historians suggest that the phrase “government of the people, by the people, for the people” may have drawn inspiration from writings he respected, including those of abolitionist Theodore Parker.

The Gettysburg dedication carried personal significance for Lincoln, who had suffered the loss of his young son Willie the year before. Willie’s passing had devastated Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and had deepened Lincoln’s empathy for other grieving families. As he stood before the graves of soldiers, Lincoln felt a profound connection with those who had also suffered loss. His words at Gettysburg honored the Union cause and gave meaning to sacrifices made by so many.

Though brief, the Gettysburg Address contained a vision Lincoln believed could reunite the country. Early in his political career, he had taken a cautious stance on slavery, initially aiming only to limit its expansion. By the time he spoke at Gettysburg, however, Lincoln saw emancipation as essential to the nation’s future. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued in January 1863, laid the groundwork for a nation free from slavery, reinforcing his call for unity.

As he left Gettysburg, Lincoln reportedly expressed doubt about the speech’s quality, telling a friend that his remarks “won’t scour”—a term farmers used for a plow that did not cut soil properly. Ironically, this modest self-assessment concealed the enduring impact his words would have. Lincoln’s straightforward language and his appeal for equality inspired generations of Americans who sought a fair and united country.

Beyond his speeches, Lincoln’s influence extended to transformative legislation. In 1862, he signed the Pacific Railway Act, which initiated the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, creating a direct route from the eastern states to California and reshaping American transportation. Additionally, he signed the Homestead Act, which offered 160 acres of public land to settlers willing to develop it, ultimately drawing millions of immigrants and shaping the American West.

Lincoln’s belief in education also led him to sign the Morrill Act, which established land-grant colleges that made higher education accessible to working-class Americans. He viewed these initiatives as essential to building a strong, unified country, believing that the government could support citizens, educate future generations, and build a foundation for economic prosperity. Though the war overshadowed these efforts during his presidency, they later defined key aspects of American society.