What Happened On May 14th?

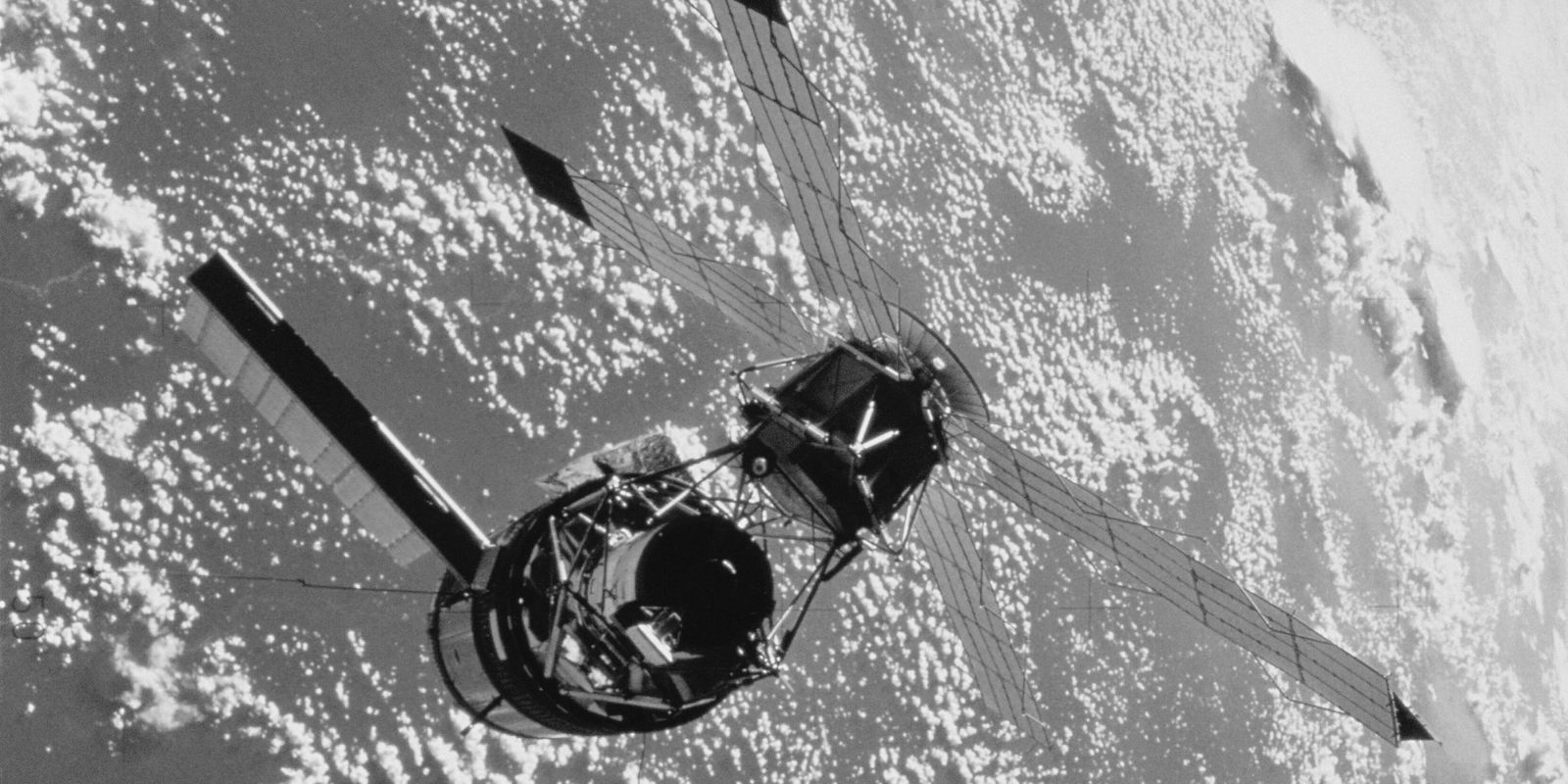

On May 14, 1973, at 1:30 PM EDT, the United States launched Skylab, its first space station, from Kennedy Space Center in Florida. As the Saturn V rocket ascended, it carried the hopes and dreams of many who had dedicated years to the project. Unfortunately, the initial moments were fraught with challenges.

Shortly after liftoff, Skylab’s micrometeoroid shield was torn away, damaging one of its solar panels. This left the station critically underpowered and exposed to high temperatures. During the next few days, NASA engineers and astronauts underwent intense efforts to devise a plan to deploy a makeshift sunshade to cool the station. The first crew, led by Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, conducted a daring spacewalk to free the jammed solar panel. Through the teams’s efforts, they successfully restored power and stabilized the Skylab’s environment.

Skylab‘s Scientists

Skylab was the brainchild of several figures within NASA and the broader scientific community. Dr. Wernher von Braun, a prominent aerospace engineer, played an instrumental role in the development of the Saturn V rocket that would eventually launch Skylab. Von Braun had a vision for space exploration that extended far beyond lunar missions. Thus, Skylab was a big step toward a permanent human presence in space.

Another key figure was Dr. George Mueller, who was NASA’s Associate Administrator for Manned Spaceflight. Mueller’s advocacy for a space station was essential in securing funding and support for the project. His efforts ensured that Skylab would not only serve as a laboratory for scientific experiments but also as a platform for the technological practices. This would be essential for future long-duration missions.

Skylab‘s Astronauts

Skylab’s team came in the form of its three-man crews, who each spent extended periods aboard the station. The first crew, launched on May 25, 1973, was comprised of Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Scientist-Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin, and Pilot Paul J. Weitz.

Conrad, a veteran of the Gemini and Apollo programs, brought invaluable experience to the mission.

Kerwin, a medical doctor, was the first physician-astronaut, tasked with studying the effects of prolonged weightlessness on the human body.

Weitz, a seasoned naval aviator, completed the trio.

The second crew, consisting of Commander Alan L. Bean, Scientist-Pilot Owen K. Garriott, and Pilot Jack R. Lousma, began their mission in July 1973.

Bean, another Apollo veteran, was joined by Garriott, an engineer and physicist, and Lousma, a skilled pilot and engineer. Their mission would further expand Skylab’s scientific horizons, focusing on solar observations and medical experiments.

The third and final crew, launched in November 1973, included Commander Gerald P. Carr, Scientist-Pilot Edward G. Gibson, and Pilot William R. Pogue. This crew set a record for the longest manned spaceflight at the time, staying in orbit for 84 days. Carr, Gibson, and Pogue’s mission underscored Skylab’s potential for extended human habitation in space.

The Apollo Telescope Mount

Skylab was equipped with the Apollo Telescope Mount, which allowed astronauts to conduct studies of the sun. These observations led to massive advancements in our understanding of solar activity and its effects on Earth. The data collected by Skylab helped scientists predict solar flares and other solar phenomena more accurately.

Skylab Space Agriculture

One of Skylab’s experiments involved growing plants in microgravity. Astronauts successfully cultivated wheat and other plants, providing valuable insights into how plants adapt to space conditions. This research was a precursor to modern space agriculture studies, which are crucial for future long-term missions to Mars and beyond.

Space Exercise?

To counteract the effects of prolonged weightlessness, astronauts on Skylab engaged in regular physical exercise. They even devised a series of gymnastic routines, using the station’s ample space to perform flips and somersaults. Not only were these exercises beneficial for maintaining physical health, but they also provided a psychological boost during their lengthy missions.

Space Hobbies

Skylab astronauts were encouraged to bring personal items to help them relax during their free time. For example, Owen Garriott brought a ham radio on board and made contact with amateur radio operators on Earth, a practice known as “ham-sat.” This helped maintain morale and provided a unique connection with people back on Earth.

Interesting Skylab Facts

Skylab operated until 1974, hosting three manned missions that yielded a wealth of scientific data and valuable experience in living and working in space. Its legacy is profound, having demonstrated the feasibility of long-duration space missions and laying the groundwork for future space stations, including the International Space Station (ISS).

One lesser-known aspect of Skylab’s legacy is its influence on space medicine. The medical experiments conducted aboard Skylab provided critical data on the effects of microgravity on the human body, informing protocols for maintaining astronaut health on future missions. This research included studies on bone density loss, muscle atrophy, and cardiovascular deconditioning, all of which remain relevant to current spaceflight missions.

Additionally, Skylab’s waste management systems allowed for future adaptation. The station employed innovative techniques for recycling air and water, which have been refined and are still in use on the ISS. These systems were essential for supporting long-duration missions and have contributed to our understanding of sustainable living in space.

Unexpectedly, Skylab malfunctioned in 1979 when debris from the space station spilled into the Indian Ocean and populated areas of Western Australia. This event highlighted the challenges of managing the end-of-life phase of space stations, a topic that continues to be relevant with the planned deorbit of the ISS.

Not only that, but the tragedy of the Columbia decades later still challenges NASA scientists to this day.