What Happened On July 5th?

On July 5, 1996, at the Roslin Institute in Scotland, Dolly the sheep was born, becoming the first mammal cloned from an adult cell. This sparked excitement and ethical debates worldwide when her birth was announced months later.

From Vision to Reality

Cloning Dolly was filled with challenges and skepticism. Scientists had long been fascinated by the idea of cloning, but success remained elusive. The team at the Roslin Institute, led by Ian Wilmut, pushed the boundaries of genetic science.

The Recipe For A Clone

They used a technique called somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). The nucleus of an adult cell was placed into an egg cell that had its own nucleus removed. The team chose a cell from the udder of a six-year-old Finn Dorset sheep. They inserted the nucleus from this cell into an egg cell from a Scottish Blackface sheep. Reflecting their sense of humor, the scientists named Dolly after Dolly Parton because they used an udder cell.

Dolly’s Birth

After 276 attempts, the team succeeded. The egg, now containing the transferred nucleus, developed into an embryo. This embryo was implanted into a surrogate Scottish Blackface sheep. Following a 148-day pregnancy, Dolly was born on July 5, 1996. Her birth was announced to the world on February 22, 1997.

Dolly was genetically identical to the Finn Dorset sheep from which the udder cell had been taken. Her birth demonstrated that specialized cells could be reprogrammed to create an entire organism. Ian Wilmut said, “We are not creating an exact copy, but rather a new individual.” The researchers kept Dolly’s birth secret for months, preparing for the media frenzy and scientific scrutiny.

Scientific & Ethical Impact?

New possibilities for genetic research emerged, including cloning endangered species, advancing medicine, and understanding developmental biology. However, it also raised profound ethical questions.

Critics voiced concerns about cloning’s impact on biodiversity, animal welfare, and the potential for human cloning. Religious and ethical debates intensified, with some arguing that cloning was unnatural and others stressing the need for strict regulatory guidelines. Bioethicist Arthur Caplan commented, “Dolly’s birth is a clarion call for a much broader discussion about the ethics of cloning.”

In response, various countries drafted laws to address the ethical and legal aspects of cloning. The UK established guidelines for cloning research to ensure responsible and ethical work. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) in the UK played an instrumental role in shaping these guidelines, ensuring that research proceeded with caution.

Dolly’s Life At The Roslin Institute

Dolly lived at the Roslin Institute, where she became an international celebrity. She gave birth to six lambs, demonstrating that cloned animals could reproduce naturally. However, arthritis and a lung disease led to Dolly being euthanized at six years old in February 2003. Her health problems sparked discussions about the long-term viability and welfare of cloned animals, prompting further research.

Behind The Lab Doors

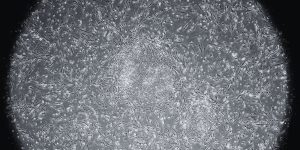

The team achieved success in cloning Dolly by carefully controlling the environment and conditions for cells and embryos. Scientists ensured that egg cells were at the right stage when the nucleus was transferred. Additionally, they closely monitored the surrogate sheep to maintain optimal conditions for the developing embryos.

Dolly’s story involved extensive trial and error. Hundreds of failed attempts preceded her successful birth. These early failures provided valuable insights that eventually led to success. Cloning required not only scientific expertise but also resilience and perseverance.

Implications For Research

Dolly’s cloning revealed the potential for new research directions. Scientists began exploring the possibility of using similar techniques to create tissues and organs for transplantation. This could revolutionize medicine by providing genetically compatible tissues for patients, potentially reducing the risk of transplant rejection.

Furthermore, cloning Dolly led to major advancements in understanding how cells can be reprogrammed. Researchers learned how specialized cells could revert to a state where they could become any cell type. This knowledge has been crucial in developing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which hold promise for treating various diseases, including Parkinson’s disease and diabetes.

Dolly’s birth spurred conversations among scientists and ethicists. Dr. Keith Campbell, a key member of the team, emphasized the breakthrough: “Dolly showed that it was possible to take a specialized adult cell and use it to create an entire organism” (Source: BBC News). This discovery challenged long-held beliefs about cell differentiation and development.

The Media Frenzy

The public reaction to Dolly’s birth varied widely. While many celebrated the scientific achievement, others expressed concerns about the ethical implications. Media coverage often focused on sensational aspects, with headlines questioning the future of human cloning and the potential for cloning extinct species.

Dr. Harry Griffin, also involved in the project, remarked on the media’s role: “The public’s fascination with Dolly highlighted the need for scientists to engage with the public and explain the real implications of our work.” This demonstrated the importance of transparent communication between scientists and the public.

Scientific Advances Post-Dolly

Following Dolly’s birth, cloning research continued to advance. Scientists cloned other animals, including cows, pigs, and dogs, each presenting unique challenges and insights. These efforts helped refine cloning techniques and improve success rates.

Dolly’s legacy also extended to stem cell research. The ability to reprogram adult cells into pluripotent stem cells opened new avenues for regenerative medicine. Researchers explored using these cells to treat conditions such as spinal cord injuries and heart disease, offering hope for new therapeutic strategies.