What Happened On July 15th?

On the hot day of July 15th of 1799, a group of French soldiers stationed in the small Egyptian town of Rosetta discovered something that would transform our understanding of ancient civilizations. Among the dusty ruins, they discovered a large, dark stone slab covered with inscriptions in three distinct scripts. This artifact, later known as the Rosetta Stone, became the key to unlocking the mysteries of Egyptian hieroglyphics. The Rosetta Stone originally formed part of a larger stone slab that likely stood about two meters tall. The broken top and bottom indicated the artifact was once a much grander monument.

The French soldiers nearly stumbled upon the Rosetta Stone by accident. Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt aimed to assert French influence in the region and included a team of scholars known as the Commission des Sciences et des Arts. This team accompanied the military to study and document Egypt’s ancient culture. During the construction of a fort near the town of Rosetta (modern-day Rashid), French engineer Pierre-François Bouchard first noticed the stone.

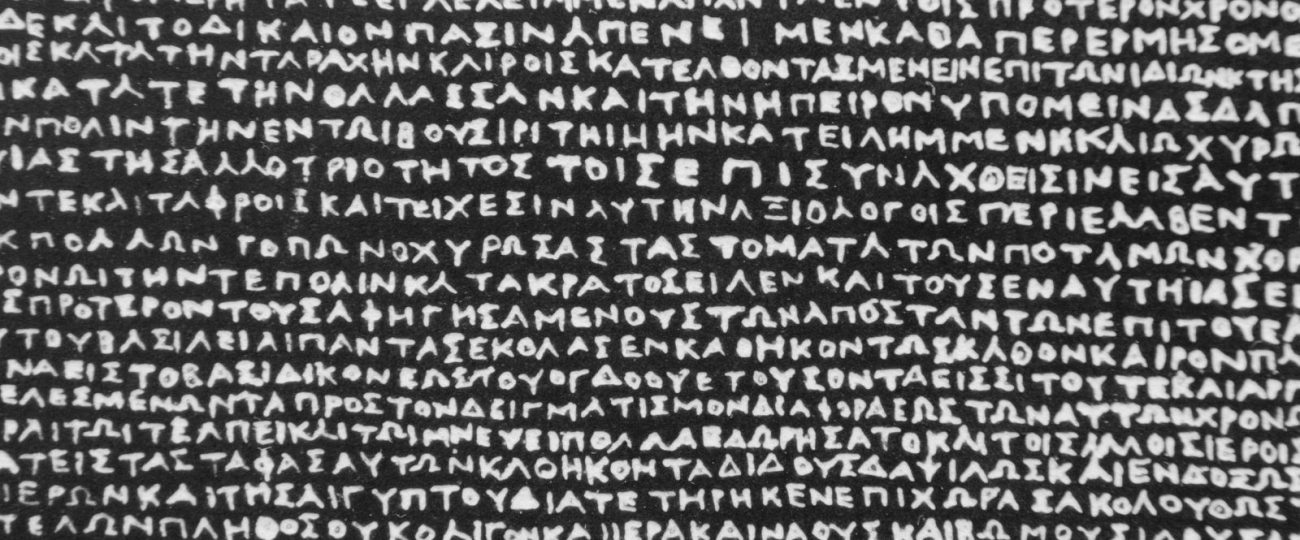

Bouchard recognized its importance and reported the find to the scholars. They immediately knew that the stone would be significant because of its inscriptions in three scripts: Greek, Demotic, and hieroglyphic. This trilingual text suggested it might hold the key to deciphering the long-lost language of the ancient Egyptians.

The Rosetta Stone, about 45 inches high, 28.5 inches wide, and 11 inches thick, consisted of granodiorite, a dark, hard rock. Clearly part of a larger monument, its fragmented state did not lessen its importance. The Greek inscription indicated it was a decree issued in 196 B.C. during the reign of Ptolemy V, confirming the royal cult of the young pharaoh. This context highlighted the close ties between religion and governance in ancient Egypt.

French scholars began their studies and quickly saw the stone as a symbol of scholarly achievement and national pride. However, the British interrupted their work by defeating the French forces in Egypt in 1801. Under the terms of their surrender, the British took possession of the Rosetta Stone along with other artifacts collected by the French.

Once in Britain, scholars presented the stone to the Society of Antiquaries of London and then moved it to the British Museum, where it remains today. Scholars across Europe eagerly sought to unlock its secrets. They could read the Greek text, but understanding the two Egyptian scripts, particularly the hieroglyphs, posed a challenge.

Thomas Young, an English polymath, identified some hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone as spelling out the name of Ptolemy. Young’s observations provided a basis for further study, but the French scholar Jean-François Champollion ultimately deciphered the hieroglyphs in 1822. Champollion’s knowledge of Coptic, the last stage of the Egyptian language, helped him succeed. He realized hieroglyphs were not just symbols but could represent sounds and syllables as well. Champollion compared the hieroglyphic and Greek texts to identify phonetic characters in the Egyptian names.

Deciphering the Rosetta Stone allowed scholars to read the vast inscriptions and texts that covered temples, tombs, and papyri. They could now comprehensively study Egyptian history. The Rosetta Stone contained a relatively ordinary decree praising the pharaoh, but its trilingual inscription made it uniquely valuable as a linguistic bridge. Its importance lay not in the content of its message, but in the way it conveyed that message through three different scripts.

Many Egyptians viewed the Rosetta Stone as a symbol of colonial plunder and called for its return. The British Museum argued that the stone was accessible to a global audience and represented Egyptian culture to the world. During its time in the British Museum, the Rosetta Stone experienced various events, including being moved to a secret location to protect it from bombings during World War I.

The Rosetta Stone attracted ongoing attention from both the public and scholars. High-resolution imaging and 3D modeling allowed researchers to study the stone’s surface in unprecedented detail. In turn, this revealed faint carvings and tool marks that had previously been missed.

Through these advanced techniques, scholars confirmed that the stone’s inscriptions were not perfectly aligned, indicating that multiple carvers had worked on it. They also discovered that the stone had been reused from an earlier monument, evidenced by traces of older inscriptions that had been chiseled away to make room for the new text.

One revelation from the stone’s inscriptions was the decree issued in 196 B.C. by priests in Memphis, affirming the royal cult of Ptolemy V. This decree not only praised the young pharaoh but also detailed the priests’ role in society and their relationship with the king. By understanding such decrees, historians gained insights into the governance and religious practices of ancient Egypt.

Initially, scholars did not recognize the Rosetta Stone as a key to understanding hieroglyphics. Only after painstaking work and the insights of many researchers did its full significance become clear.