What Happened On August 20th?

On August 20, 1619, a ship carried the first enslaved Africans and arrived at Point Comfort, near the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia. This day marked the beginning of a system that deeply shaped the social, economic, and cultural landscape of what later became the United States. The arrival of these 20 to 30 African men and women signaled the start of a tragic chapter that grew into the institution of slavery in America.

The English privateer ship, White Lion, anchored at Point Comfort after capturing a Portuguese slave ship, the São João Bautista, off the coast of Mexico. The Portuguese vessel had originally set sail from Luanda, in present-day Angola, with enslaved Africans intended for the Spanish colonies. However, the White Lion, along with another English ship, the Treasurer, intercepted and seized part of this human cargo, bringing them to Virginia. The Africans aboard the White Lion represented only a small fraction of the hundreds who had been captured in Africa, many of whom did not survive the brutal journey across the Atlantic. The original group of enslaved Africans had been part of a much larger convoy, many of whom were taken by other privateers and ended up in different parts of the Americas.

When the White Lion arrived at Point Comfort, the English settlers traded food and supplies for the captured Africans. The fate of these Africans remained uncertain as the settlers forced them into a world completely foreign to them. Initially, the English settlers treated them as indentured servants, similar to the Europeans who had come before them, but the reality of their lives in Jamestown quickly became much harsher. As time passed and the demand for labor grew, these individuals and their descendants endured lifelong bondage, with the legal and social systems increasingly defining their status as enslaved people. In the early years, the legal status of these Africans was ambiguous, and in some cases, they were able to negotiate terms of labor that allowed for eventual freedom—a practice that was quickly curtailed as laws solidified the institution of slavery.

The settlement, founded in 1607, struggled with high death rates, a tough environment, and a constant need for workers to keep its economy growing. A few years earlier, the introduction of tobacco farming had transformed the colony’s prospects, making labor even more critical. The English settlers initially relied on indentured servants from England, but the arrival of enslaved Africans provided a new source of labor. This shift laid the foundation for a system of slavery that eventually dominated the Southern economy and deeply affected American society. Tobacco farming, being labor-intensive, rapidly depleted the soil, which in turn increased the demand for new lands and more enslaved labor, further entrenching the system of slavery.

The colony’s leaders recorded the event, noting the arrival of “20 and odd Negroes” as significant. Yet, they did not fully grasp the long-term impact of this event. What began as a practical solution to a labor shortage evolved into a complex system of racial slavery that shaped the identity of the emerging nation.

In the early years following this event, some of these Africans gained their freedom and became landowners. Anthony Johnson, who arrived in Virginia in 1621 as an enslaved African, eventually earned his freedom and acquired a substantial amount of land. By the 1650s, Johnson was not only a free man but also a successful landowner with his own indentured servants. However, this period of relative freedom for some Africans ended as the colony’s legal system increasingly enforced racial slavery, stripping away the rights and freedoms of Africans and their descendants. After Johnson’s death, a court ruling declared that his land would be taken from his family because they were Black, illustrating how legal structures evolved to disenfranchise even those Africans who had managed to prosper.

As the years passed, the legal status of Africans in Virginia grew more restrictive. Initially, the status of Africans in the colony was somewhat flexible, with some gaining freedom after a period of servitude, similar to their European counterparts. However, by the mid-1600s, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed laws that solidified the institution of slavery based on race. One of the first such laws, passed in 1662, decreed that the status of a child would be determined by the status of the mother, ensuring that the children of enslaved women would also be enslaved, perpetuating the cycle of slavery.

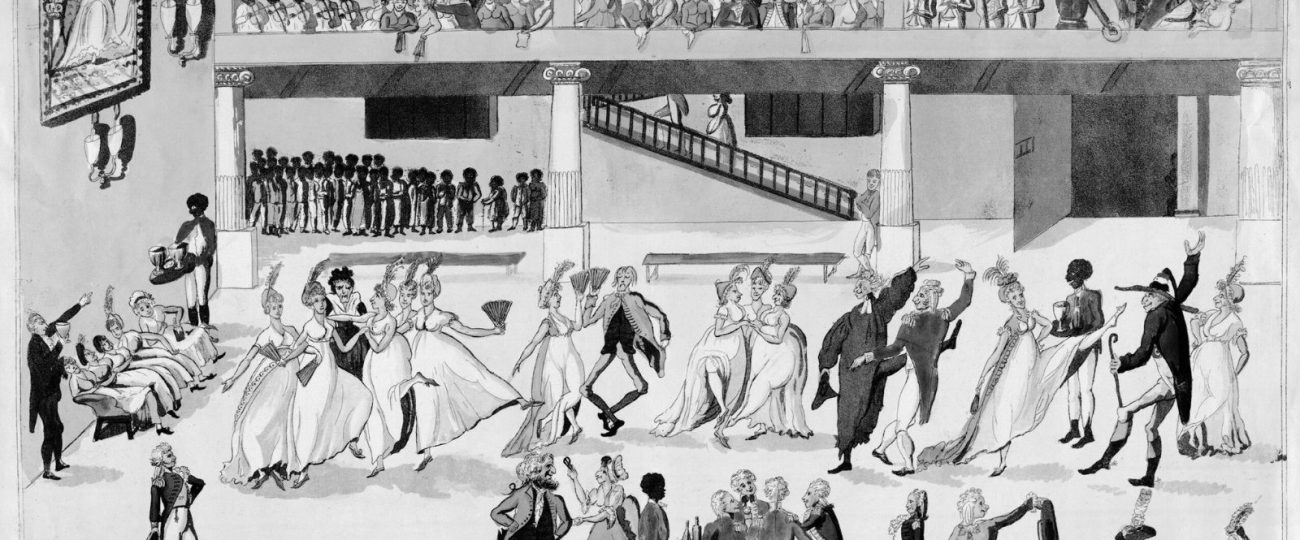

The arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Jamestown profoundly impacted the colony’s culture. The Africans brought rich traditions, languages, and knowledge that influenced the development of African American culture. For instance, many farming techniques and crops that became staples in the American South, such as rice cultivation, were introduced by enslaved Africans who had practiced these methods in their homelands. These Africans used specific farming techniques, like the “task system” in rice cultivation, which came directly from West Africa and demonstrated the deep agricultural knowledge they brought with them. The introduction of the banjo, an instrument that originated in West Africa, became a key element in American folk music, illustrating how African culture began to blend with other traditions in the New World.

Despite the oppressive conditions, the early Africans in Jamestown showed resilience and adaptability and established a rich cultural heritage. Enslaved Africans forged community bonds through shared language, religion, and resistance, which provided a sense of identity and strength in the face of unimaginable hardship. Enslaved Africans used coded songs and stories as a form of resistance and communication, subtly passing along messages and preserving their cultural identity under the watchful eyes of their oppressors. The spiritual “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” for example, was later used as a guide for enslaved people seeking freedom through the Underground Railroad, showing how these early cultural practices evolved into tools of resistance.

Many Africans initially practiced their traditional religions, but they gradually encountered Christianity through the English settlers. Enslaved Africans often adapted Christian teachings to align with their own beliefs, creating a distinct religious practice that emphasized themes of liberation and hope.

This blending of African spirituality with Christianity laid the foundation for African American religious traditions, which later played a crucial role in movements for social justice and civil rights. The “invisible church,” where enslaved people worshipped in secret gatherings away from the eyes of their enslavers, showed how religion provided both comfort and a means of resistance. These secret gatherings often took place in hush arbors—hidden clearings in the woods—where enslaved people could worship freely, away from the scrutiny of plantation owners.