What Happened On August 18th?

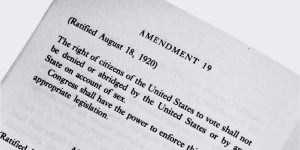

On August 18, 1920, Tennessee’s state legislature met in Nashville to vote on the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. This vote determined whether women across the United States could finally participate in elections. The atmosphere inside the Tennessee State Capitol grew tense as lawmakers prepared to decide on an issue that had divided the country for years.

By this time, 35 states had already approved the amendment, but one more state’s approval was needed to make it law. Tennessee became the final battleground, and the vote in its House of Representatives either allowed the amendment to pass or delayed women’s suffrage indefinitely. As the roll call began, supporters and opponents of the amendment held their breath, knowing the result would be close.

Harry T. Burn, a 24-year-old lawmaker from McMinn County, cast one of the most critical votes that day. Burn had planned to vote against the amendment, siding with those who opposed women’s suffrage. However, just before the vote, he received a letter from his mother, Phoebe “Febb” Burn, urging him to support the amendment. Her words, “Hurrah and vote for suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt,” persuaded Burn, and he voted in favor of ratification. His unexpected “Aye” broke a 48-48 tie, allowing Tennessee to pass the 19th Amendment.

After the vote, chaos erupted in the chamber. Lawmakers who opposed the amendment expressed shock at Burn’s decision and tried to delay the official ratification by leaving the room to prevent a quorum. Security guards blocked their exit, and after several tense hours, the Speaker of the House, Seth Walker—who had also opposed the amendment—moved to end any further attempts to reconsider the vote, securing the victory for those in favor of women’s suffrage.

Tennessee’s decision on August 18, 1920, didn’t just settle the fate of the 19th Amendment; it changed the course of American history. Suffragists who had fought for decades to secure the right to vote finally saw their efforts succeed. However, this victory in Tennessee came only after a hard-fought battle. Suffragists faced strong opposition not only from within the legislature but also from powerful groups who believed that allowing women to vote would disrupt society. One lesser-known fact is that suffragists and anti-suffragists occupied different floors of the Hermitage Hotel in Nashville, turning it into a command center for both sides. The hotel became the epicenter of intense lobbying, with each side trying to sway the undecided lawmakers.

The debate in the Tennessee House grew intense. Those against women’s suffrage argued that giving women the right to vote would harm families and weaken society. They worked hard to convince lawmakers to vote against the amendment, using everything from political pressure to bribes. Supporters of women’s rights, however, argued that denying women the vote violated the principles of democracy. They filled the statehouse, many wearing white dresses as a symbol of their cause, and waited anxiously for the outcome. Interestingly, the suffragists wore yellow roses to signify their support for the cause, while the anti-suffragists donned red roses. The sight of lawmakers with yellow or red roses pinned to their lapels made it clear where they stood on the issue.

Suffragists in Tennessee won through careful planning and grassroots efforts. Carrie Chapman Catt, a leading figure in the movement, organized a nationwide campaign to win approval for the amendment. In Tennessee, she and other leaders worked tirelessly to persuade undecided lawmakers, appealing to their sense of fairness. Local women’s clubs also played a key role in persuading important lawmakers to support the amendment. These clubs organized letter-writing campaigns and visits to lawmakers, directly influencing the final vote. Many of these women’s clubs, often dismissed as mere social gatherings, became powerful organizing hubs that rallied support for the amendment at a grassroots level. The members of these clubs often used their connections to influence lawmakers directly.

Tennessee’s approval of the 19th Amendment did more than give women the right to vote; it ended a long struggle that had started with the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. Women like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Ida B. Wells led the charge for suffrage, often facing ridicule and even imprisonment. By 1920, the movement had gained unstoppable momentum, with women across the country rallying for their rights. Had the state not ratified the amendment, the entire suffrage movement could have faced a significant setback, with years potentially passing before another state would have taken up the cause.

The victory in Tennessee, however, also revealed deep divisions in American society. While the amendment gave millions of women the right to vote, many Southern states, including Tennessee, quickly passed laws to keep African American women and men from voting, using tactics like poll taxes and literacy tests. These actions showed that the fight for full voting rights was far from over and would continue for many more years. African American women played a vital role in the suffrage movement, particularly in organizing and advocating for the right to vote. However, they often faced discrimination from within the movement itself, as some white suffragists sought to distance themselves from issues of race to gain broader support.

Harry T. Burn’s vote became a subject of discussion long after the events of August 18, 1920. Burn faced criticism from his constituents, many of whom opposed women’s suffrage. However, he defended his decision, saying that he believed it was the right thing to do and that his mother’s letter had influenced him. In later years, Burn’s vote came to symbolize how personal beliefs and political actions could shape history. Burn kept his mother’s letter for the rest of his life, seeing it as a reminder of the importance of listening to one’s conscience, even in the face of public pressure.