What Happened On November 6th?

On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States, a victory that altered the course of American history. He won just under 40% of the popular vote and secured 180 of the 303 electoral votes, emerging victorious in a four-way contest. His election highlighted the country’s stark divisions, especially between the North and South. Lincoln’s name did not appear on ballots in ten Southern states, underscoring the deep regional tensions. The election triggered a sequence of events that would soon lead to the Civil War.

South Carolina responded almost immediately. By December 1860, the state had officially seceded from the Union, becoming the first to take this drastic step. Other Southern states followed, forming the Confederate States of America before Lincoln even took office. Southern leaders viewed Lincoln’s anti-slavery stance as a threat, despite his repeated assurances that he would not interfere with slavery where it already existed. The South feared, however, that his administration would prevent the expansion of slavery into new territories, which would limit their political power.

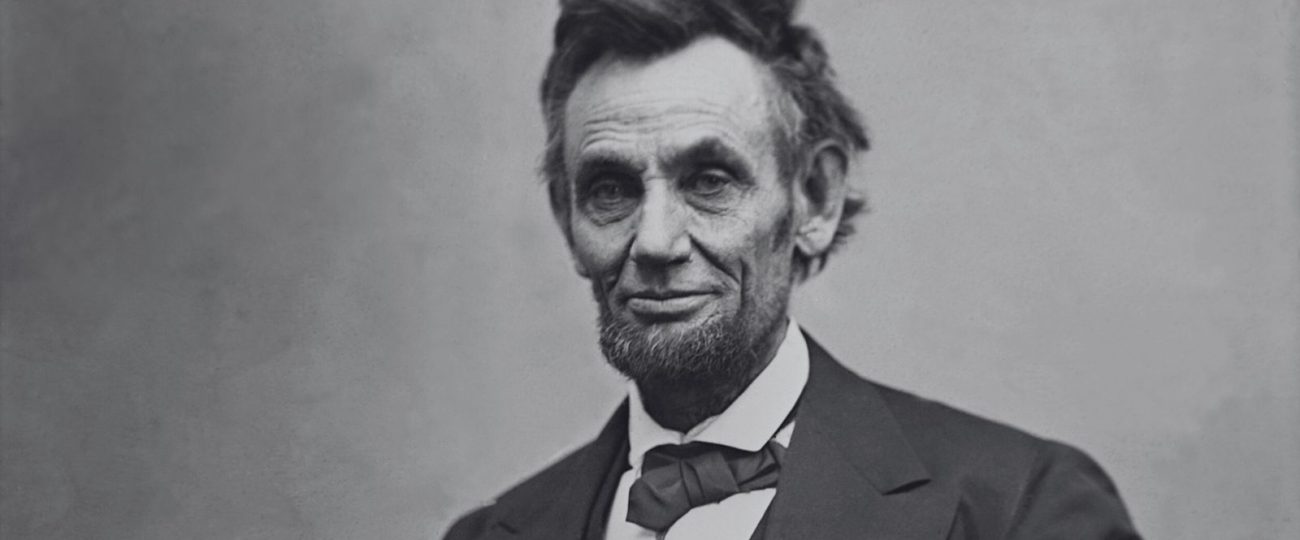

Lincoln’s journey to the presidency began with humble roots. Born on February 12, 1809, in a log cabin in Kentucky, he faced poverty throughout his childhood. His mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died when he was nine, a loss that left a lasting emotional impact. His father remarried, and Lincoln’s stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston, encouraged him to pursue education, even though his formal schooling was limited. Lincoln borrowed books from neighbors and taught himself. Aesop’s Fables and the Bible were some of the texts that shaped his thinking and helped him become a skilled orator.

Before entering politics, Lincoln worked a variety of jobs, including splitting logs, clerking in a store, and operating a general store. He also worked as a flatboatman, traveling down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. On one trip, he witnessed a slave auction, a moment that deeply affected him. Though he did not express strong abolitionist views at that time, this experience influenced his growing moral opposition to slavery.

After studying law independently, Lincoln passed the bar in 1836 and began practicing law in Springfield, Illinois. He gained a reputation for his sharp legal mind, often using logic and evidence to win cases. In a famous incident, Lincoln used an almanac to prove that a witness could not have seen a crime as claimed due to the moon’s position. This defense led to the acquittal of his client, showcasing Lincoln’s ability to think critically under pressure.

Lincoln’s rise to national prominence occurred during his 1858 Senate campaign against Stephen A. Douglas. Although Lincoln lost the race, the debates between the two men attracted national attention, particularly Lincoln’s arguments against the expansion of slavery. His “House Divided” speech, where he famously said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” positioned him as a strong defender of the Union. This attention propelled him to become the Republican Party’s presidential candidate in 1860.

The Southern states viewed Lincoln’s election as a direct threat to their future. Although he did not advocate for the immediate abolition of slavery, they feared his policies would eventually lead to its destruction. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy, with Jefferson Davis as their president.

As Lincoln assumed office, he inherited a nation on the brink of war. Despite his efforts to calm tensions by affirming that he had no intention of abolishing slavery where it already existed, conflict appeared inevitable. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina, igniting the Civil War.

Throughout the war, Lincoln took decisive action to keep the Union intact. In 1862, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all slaves in Confederate-held territories were free. Although it did not immediately free all enslaved individuals, it shifted the Union’s war effort. The fight was no longer just about preserving the nation—it was now about ending slavery. Nearly 180,000 African American soldiers served in the Union Army by the war’s end, contributing significantly to the Northern victory.

Lincoln faced countless challenges throughout his presidency. Radical Republicans urged him to push more aggressively for emancipation, while Northern Democrats called for an end to the war, even if that meant allowing the South to secede. Despite these pressures, Lincoln remained committed to preserving the Union. His re-election campaign in 1864 initially looked uncertain, as the war dragged on and public morale waned. However, Union victories, including General William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, helped secure his re-election.

Lincoln demonstrated empathy and personal connection with soldiers during the war. He visited hospitals and battlefields, spending time with wounded soldiers and listening to their stories. His compassion extended even to those soldiers who faced court-martial for desertion. On multiple occasions, Lincoln intervened to pardon young soldiers, understanding the immense toll the war had taken on them.

In early 1865, Lincoln successfully pushed for the passage of the 13th Amendment, which permanently abolished slavery in the United States. He recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation alone might not withstand legal challenges after the war, so he worked tirelessly to ensure that the amendment became law. Its passage secured the end of slavery once and for all.

Just days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Union forces at Appomattox Court House, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865 at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Booth’s assassination plot, part of a larger conspiracy, aimed to destabilize the Union government in its moment of triumph. Lincoln died the next morning, making him the first U.S. president to be assassinated. Interestingly, in the weeks leading up to his assassination, Lincoln had spoken about vivid dreams in which he saw his own death, sharing these eerie premonitions with friends and family.