What Happened On October 27th?

On October 27, 1904, the streets of New York filled with excitement as residents gathered to experience the city’s first subway ride. At exactly 2:35 PM, Mayor George McClellan Jr. personally drove the initial subway train from City Hall to 103rd Street before stepping aside for the motorman to take over. By the end of the day, over 150,000 passengers had paid their five-cent fare to travel the 9.1-mile route from lower Manhattan to Harlem. The opening of the subway promised a faster, more efficient way to move through the city, transforming the daily lives of New Yorkers.

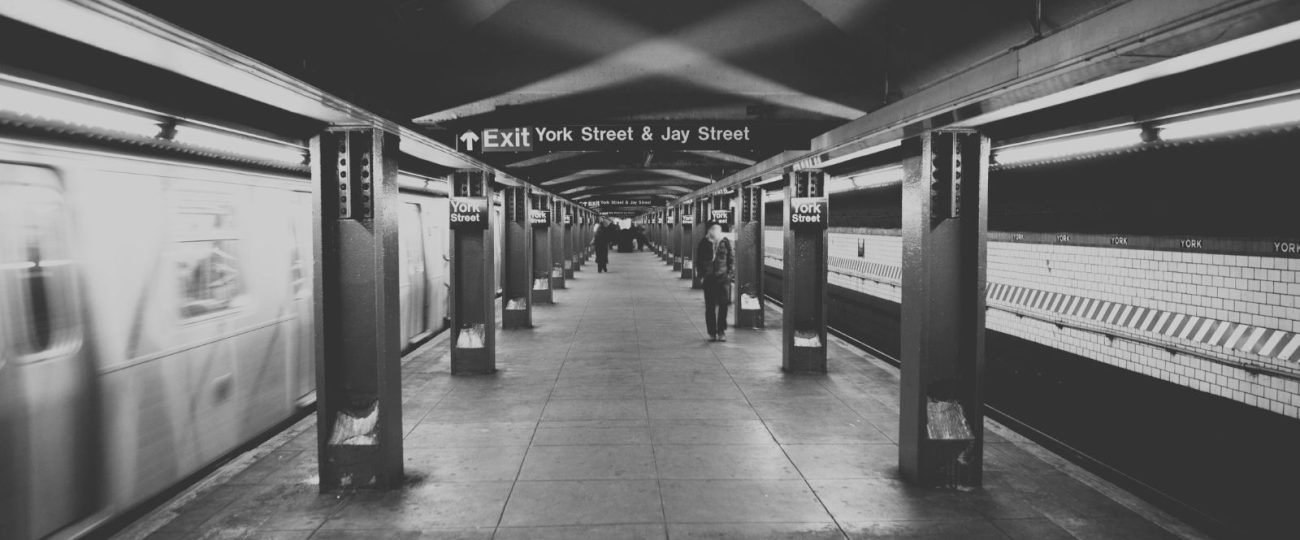

The stations, lined with white tiles and lit by electricity, created a clean, modern feel. Riders marveled at the speed and comfort compared to the overcrowded elevated trains they were used to. The subway immediately stood out for its efficiency, offering a smoother journey beneath the bustling streets above. The system represented a leap forward for a city that had been struggling to manage its growing population and congested streets.

The subway’s construction, which began in 1900 under the direction of engineer William Barclay Parsons, was daunting. Crews worked under dangerous conditions, often using dynamite to blast through Manhattan’s hard granite bedrock. Five workers lost their lives, but the urgency of the project outweighed the risks. The city’s growing population demanded better transit options, and surface-level transport had become inadequate. The subway presented a long-awaited solution to the city’s overcrowding problem.

The vision for underground transit had existed decades before the subway became a reality. In the 1870s, inventor Alfred Beach had constructed a pneumatic subway beneath Broadway, using air pressure to move a small train. Though the system ran for only 300 feet, it demonstrated the potential for underground travel. Unfortunately, political resistance and financial constraints cut the project short. By the early 20th century, however, the city had advanced enough to build a full-scale subway network that would permanently alter urban commuting.

The subway’s initial success led to rapid expansion. One of its earliest extensions connected Manhattan to Brooklyn via the Joralemon Street Tunnel, the first underwater tunnel built for transit. This development reduced commute times between the boroughs and encouraged population growth in Brooklyn, as it made living there more convenient for those working in Manhattan. As a result, more people saw Brooklyn as a desirable place to live, and the subway became essential to their daily routines.

While the subway provided convenience, early passengers faced discomfort during the summer months. With no air conditioning, temperatures underground often soared. Ventilation grates, installed at street level to release hot air, unintentionally blew bursts of warm air onto pedestrians. It took years for proper cooling systems to be implemented, which eventually made subway travel more comfortable during the hottest months of the year.

The “cut-and-cover” method used to construct much of the original subway caused significant disruption above ground. Workers dug trenches along major streets, laid tracks, and then rebuilt the roads, which led to months of dust, noise, and traffic congestion. Businesses along these routes struggled as foot traffic dropped, and residents had to contend with the chaos. However, the promise of a faster and more reliable transit system kept public support high. New Yorkers remained hopeful that the long-term benefits would outweigh the temporary inconveniences.

City Hall station, the starting point of the subway’s first ride, became a symbol of the system’s grandeur. Its elegant vaulted ceilings, intricate Guastavino tiles, and chandeliers made it one of the most beautiful stops on the line. Despite its stunning design, the station closed in 1945 because it could no longer accommodate longer trains. Although it no longer serves passengers, the station remains preserved, a hidden architectural gem that subway enthusiasts can still view through special tours.

Real estate developers played a key role in pushing for subway expansion. Recognizing that property values would rise around new stations, many developers actively lobbied for subway lines to run through their neighborhoods. This influenced the growth of various areas across New York, spurring rapid development in places that had once been considered too far from the city center. As a result, neighborhoods far beyond Manhattan thrived as they became more accessible to the city’s core.

During the Cold War, several subway stations were designated as fallout shelters, stocked with supplies in case of nuclear attack. Beyond just moving people, the subway played a critical role in ensuring the city’s preparedness for various emergencies.

Over the decades, technological innovations improved the subway’s operations. The installation of automatic signals in 1918 increased the system’s efficiency and safety, allowing trains to run more frequently and reduce delays. In the mid-20th century, the introduction of fluorescent lighting made the stations brighter and safer for passengers. Later, the switch to the MetroCard system in the 1990s replaced the token-based fare system, modernizing the way New Yorkers accessed the subway and speeding up the entry process for millions of daily riders.

The subway’s expansion into the Bronx and Queens during the 1920s transformed once-remote neighborhoods into thriving residential areas. The convenience of fast, reliable transportation encouraged people to move farther from Manhattan while still maintaining an easy commute to work. The growing network reshaped the city’s geography, turning distant boroughs into vital parts of New York’s urban fabric.

Today, the New York City subway spans more than 665 miles, connecting all five boroughs and serving millions of riders daily. What began with just 28 stations in 1904 has grown into one of the world’s largest and most vital public transportation systems. The subway’s continued growth and adaptation to meet the needs of a changing city make it indispensable to the daily lives of New Yorkers. It stands as a testament to the city’s enduring drive to improve and innovate, ensuring that millions can move efficiently through the metropolis.